Research comics for science communication: Interview with Dr. Ulrike Hahn

“Next to being communicative or a didactic means, I see research comics as having the potential to be more open-ended, process oriented, and transformative. For example, a research comic can be about the researchers’ questions or the research participants’ questions. Or it could include blank spaces, meant to be filled in by the viewer or reader of the comic. This opens up possibilities for comics to move beyond being a ‘communicative tool’ of research. Research comics are not necessarily only intended for the person ultimately engaging with it. They can include sensemaking processes for the creator of the comic. I believe that working on comics, or other art, is not just about creating a finished outcome or achieving a solution, but it is about the process, involving brainstorming, sensemaking, reflection, questioning, collaboration, etc.”

The following text is the accepted version of the published article in the journal Multimoadality & Society: Hahn, U., Augé, A., & Butler, R. (2025). Research comics for science communication: Interview with Dr. Ulrike Hahn. Multimodality & Society, 0(0). https://doi.org/10.1177/26349795251345278

Abstract: Dr Ulrike Hahn is interviewed about her research in the field of climate-related visual art. In particular, her work currently involves turning the insights and studies of other researchers into research comics. In addition to Dr Hahn’s current research, the interview draws on how research comics can help to make academic claims credible on the one hand, and accessible to the wider public on the other hand through the portrayal of characters to whom the audience can relate. These multimodal factors contribute to the authority of both academic research and the comic format.

Introduction

In this practitioner reflection, Dr Ulrike Hahn is interviewed by Senior Lecturer Robert Butler and Associate Professor Anaïs Auge about her research in the field of climate-related visual art and her science communication project on research comics. The interview especially focuses on her work of turning the insights and studies of her PhD and the research of other scientists into research comics. The aim of this reflection is to explore why and how research comics, which are multimodal and offer interesting questions on authority, can offer a creative and visual experience with research. Its characteristics can

be goal-oriented, with the aim of making research accessible to a different public, and process-oriented offering a creative experience with one’s research.

Robert Butler: Dr Hahn, could you tell us about your current research project which brings together science and art?

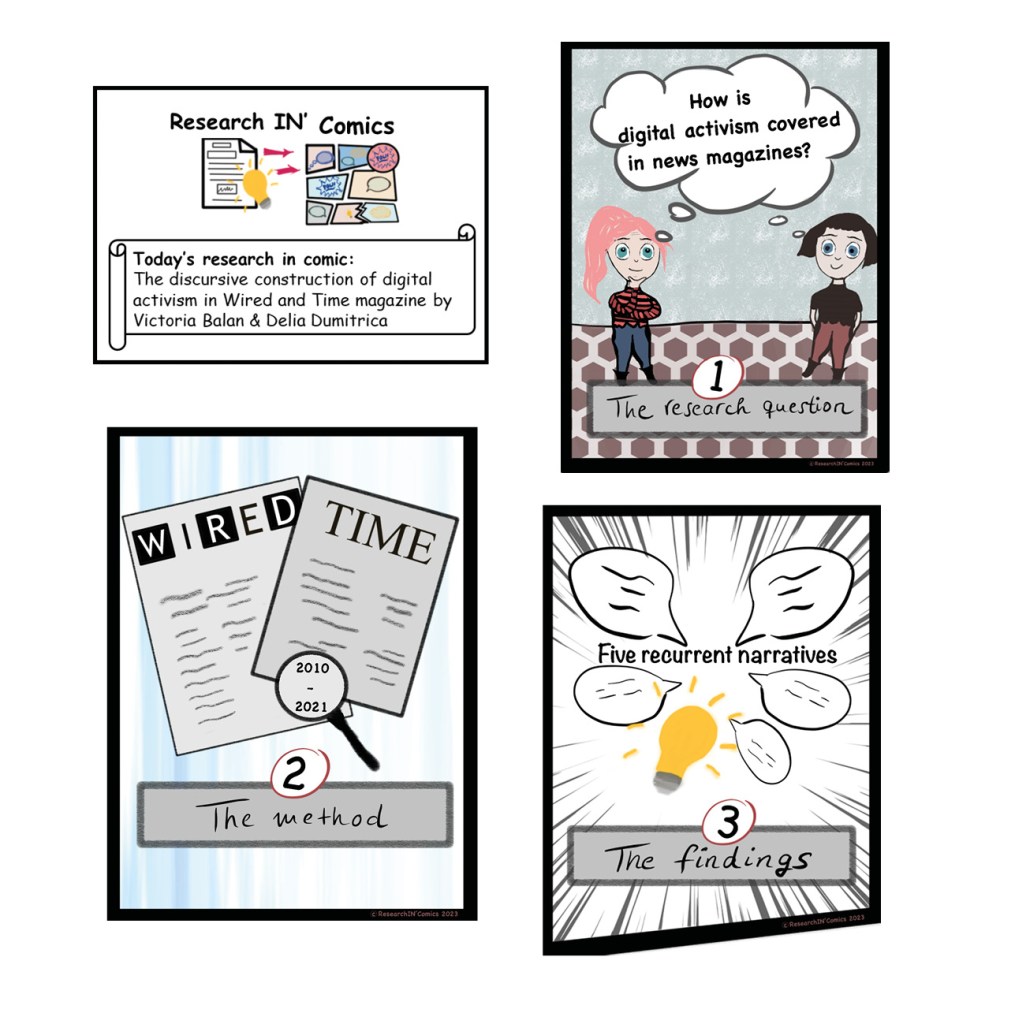

Ulrike Hahn: My PhD is all about climate-related visual art, with four studies delving into how the visual arts connect to climate change. For example, my research has involved interviewing artists about their goals and audiences. Some of them act as public intellectuals, synthesizing and analysing climate change topics, addressing a broader public and acting as activists. Additionally, I am working, next to my PhD, on turning those insights and the studies of other researchers into research comics. In Figure 1, you can see the first panels of a research comic. In this example, I followed the structure of an academic publication, which often moves from the research question to the methodology and then to the findings section. Research comics do not have to necessarily follow this set-up, but I feel it certainly is a very straightforward and easy to grasp approach. It definitely helps to start out with a question as this may trigger interest in the topic. I am also facilitating participatory workshops in which researchers can create their own comics about their research. Comics offer a different take on science communication. In addition to the traditional publication, they allow us also to have a creative and visual experience with research through a sequence of images. Comics are no longer only used in the entertainment realm. Although not without encountering challenges or involving complexities, they have received some attention in science communication and education (Cohn, 2021; Degand, 2022). They are definitely not something that everybody in academia will know about or they may not yet be included in many journals or on a journal’s website, so there are still some questions surrounding the genre. Where is this an accepted format? What do people think about it in the academic community? I find it very interesting to go into this alternative science communication approach through comics. It is a novel way of commanding intellectual authority through creative means.

Anaïs Augé: Sometimes, the scientific claims that are included in some comics feel either absurd, or the claims could be disputed, mainly because sometimes they are offered by the scientific community. Yet because of the format of the comic, I find I pay more attention to the message. Is this something you have thought about in your own work when you write comics and draw comics?

Ulrike Hahn: When you design them, you need to specify the context and translate academic language into the visual and written language of a comic. This is difficult to achieve, especially with academic language and concepts – which are sometimes hard to explain – and then to find metaphors and use character-driven stories. It is complicated because another approach is needed to make the context clear and it is vital to avoid making the comic misleading, as this could compromise the credibility or authority of the comic maker. Firstly, when we make a research-based comic, we make a link to the study so that you can actually read the text (if there is a published paper on the topic). If you are interested in the comic, it is probably because you find the portrayed topic interesting and you can actually go to the publication to discover more about it. A link to the published paper also helps to underline that the comic is built on a reliable source of information and that the researcher has the expertise and is an authority in the depicted topic area. Secondly, it is crucial to specify the context in which the research has been conducted, for example: if the research was done in the Netherlands or France. The knowledge of the publication is inevitably more compact in a comic, but it still needs to be accurate. That is a very important task to actually do when making the comic and is definitely something to keep in mind. Thirdly, comics are so much about character-driven stories. How do you portray the people in that comic? Who is actually talking? Who is represented? Who is also left out? When I started this project in 2021, it seemed quite straightforward to make a research-based comic, but, in reality, it is a more difficult procedure. I read a lot about visual communication and comics in the past years, and I made numerous comic drafts. Many aspects of my own experience with comics, be it making them myself or guiding others through the process, were supported by insights of articles and books that I read, for example by Darnel Degand on how to evaluate comics (in an educational context) (Degand, 2022), or by Willemien Brand on visual communication (Brand, 2019, 2022). The process and end result of comic-making are, I think, very rewarding because you definitely have something interesting in a format that is fun and visually creative, and which can be accessible. Its comprehension depends on several aspects though, such as if the content is clearly addressed or if the panels are logically presented (according to the audience). It can then become possible to converse with those who are outside of academia about the key research that has been undertaken or the questions that are asked in a research project. This makes it very rewarding, but it definitely takes time to get there, with a lot to learn on the way.

Anaïs Augé: When you work on comics and art, do you target a specific audience? If a thesis, for example, were written in comic format I think a lot more people would actually be interested in reading it, and not just the jury and specialists. Is it something that you consider in your work?

Ulrike Hahn: A very good question about the audience – this is where the original idea came from. When I started working on my PhD in 2019, I asked myself who would read my thesis: my supervisors, and probably some experts in the field who are interested in climate-related art. It may also be of interest to artists and institutions that work on the climate crisis, but who else is going to read it? So that was the starting point for me to think about science communication and how I could turn my research into something different and reach out to a different audience – for example, an audience outside of academia or art world participants who are not as connected to eco-social themes. Of course, it is also interesting to see in academia that communicating through the medium of comics can be accepted more, at least in some areas. For example, I recall a conference in the Netherlands with an illustrator actually there to engage with the researchers. He was basically drawing and sketching about the conference. Furthermore, through the workshops on research comics that I lead each year – where I guide researchers through the creation of their very own research comics – I am able to see what they do with their own research comic. Do they use it on social media? And which other channels do they use to show their research comic? What I also find fascinating is that we cannot just assume that any comic is universally comprehended, as Neil Cohn insightfully explains in his book “Who understands comics?” (Cohn, 2021).

Robert Butler: What part does humour play? Does the text necessarily say what is in the image, and do text and image complement one another? Is there an information gap in the text so the image gives you what is not in the text? Does the image miss something that the text confirms?

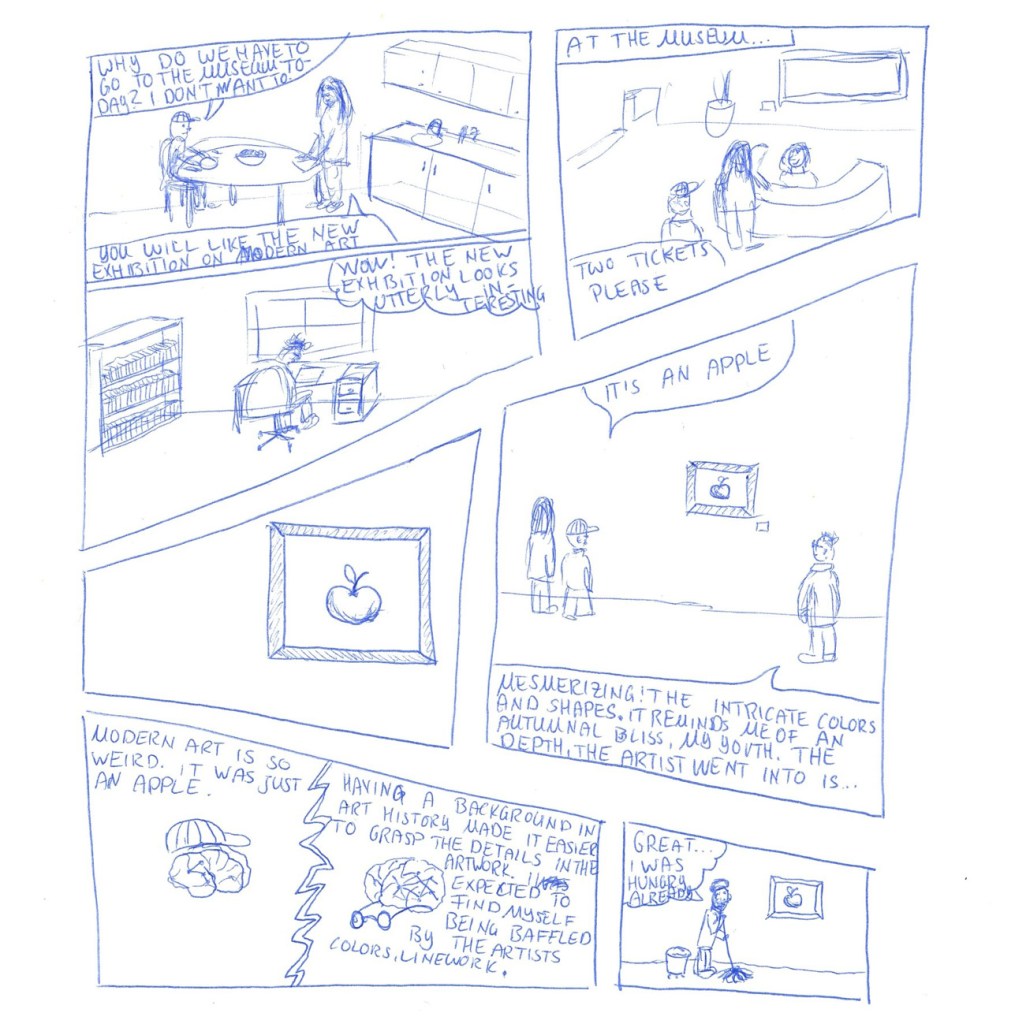

Ulrike Hahn: Multimodal combinations between visual and verbal languages play a big role in comics. Darnel Degand offers a fascinating – visual and textual– summary on comics and their characteristics, including multimodality (Degand, 2022). Another interesting read on this is the above-mentioned book “Who understands comics?” by Neil Cohn (Cohn, 2021). One can try to convey a message of a comic through the verbal and visual modality in a balanced way, but it may happen that it is expressed more by the visual modality, or more by the verbal modality. Away to find out which one carries more weight is, for instance, described by Neil Cohn (Cohn, 2021). By deleting the images, and deleting the text, one can observe how that affects the message of the comic: in which situation do you lose more information? You can try this for the very first research comic draft, which was made by a workshop participant (see Figure 2). You might find that the text appears quite important to tell the story in this draft. And you might also find that some images are very telling. For example, the museum context in the middle of the comic is quite clear from the image. This first research comic draft was a very good start to then further edit and finetune it. What I try to do in the comics I design, and what I tell people who take the workshops on research comics, is to attempt to let the images speak for themselves, while the text helps to support the image, giving the reader additional – textual – information about what is in the comic. For example, in comics, you have the caption underneath that can give you some kind of context or maybe even a headline for the image that you see. And then you can also of course use speech bubbles, as can be seen, for example, in Figure 2. These techniques for incorporating text in the image allow you to tell the story further by having the characters talk to each other. I do think it is a very good idea to provide additional information or to leave the viewer or reader with a link, as some will want to know more about it and will then follow it up. I see text and images as complementing one another. The text (or image) might give away information that is not portrayed in the image (or not told in the text). Of course, it can also happen that text and image overlap in what they convey. Some comics might end up stronger in visual or stronger in verbal language. Humour can play a role in the comics, but I wouldn’t see it as a prerequisite of a research comic.

Robert Butler: So the text or image provides additional information. It supports the image or text, in other words. Could I ask you about the research topics which you are turning into a comic format linked to the climate crisis? Are these climate-related themes quite varied and even related to other areas of academia, or are they mostly in the area of sustainability and the climate crisis?

Ulrike Hahn: The studies of my PhD that I turn into comics address climate change. One of the comics in progress is about an artwork analysis that was part of my PhD. All the artworks were on climate change, so this one is a comic based on an artwork analysis and what came out of that in terms of how the artworks related to activism and addressing the structural causes of the climate crisis. Another comic is expected to be on the engagement of exhibition visitors. It addresses questions including: who is going to these exhibitions? Are the visitors already particularly committed to the cause? Another research comic that I designed is based on interviews that I conducted with artists who are all working on climate-related art and then what materialised from those talks with these thirty artists talking about climate change and how they address their network.

Robert Butler: This raises questions about access to knowledge and how multimodality facilitates this. Is your methodology transferable to other contemporary issues, such as another study which may focus on a social or political crisis?

Ulrike Hahn: The researchers for whom I organise the workshops come from different areas of research – philosophy, medicine, psychology – and they work on different topics in their own research. And I have seen the methodology work in these other areas and topics as well. Nevertheless, there are also challenges when attempting to turn research into research comics. For example, regarding how to ‘translate’ academic language into lay terms and finding suitable metaphors. In the workshops, we walk through at least three questions, which are based on questions that Willemien Brand describes in her book on visual communication in business settings (Brand, 2019). I adapted some of these for the research comic context. By answering these questions, the participants get closer to addressing these challenges: (1) Why do I want to make a research comic, (2) Who is the audience of the comic, and (3) What is the story or core message of the comic? By doing creative exercises, engaging in an iterative process, and testing out their comic draft with others, participants get closer to creating their own research comics. Of course, there are many more details to the “how” of the workshop, too many to list them here. If the reader of this interview is interested to hear more, please feel free to get in contact with me. I am happy to connect on this.

Anaïs Augé: The key seems to be conveying something I think both important and relevant to these new audiences. I do find that fascinating, actually how you can reach out to them and expand the public scope of science. When people in different communities and workshops see your artwork – both your comics and abstract pieces – do they have like specific reactions, and do you build on these reactions in your own artwork?

Ulrike Hahn: There was indeed one moment, a few years ago, early on at the time when I started to organise participatory, creative workshops– where people come together and they would not only see my art and creative things that I was doing, but they would also engage in their own creative activity in the workshop. The first one I did was about the circular economy. When I showed my work, people had very different responses to it, which I find really interesting because there is not just one message or one takeaway from a piece of art. I think it is important to facilitate open-ended explorations or to allow for ambiguous messages – people will have different interpretations or different responses to what they see in any case. The reactions in the workshops were quite varied responses in terms of what they saw in a piece of art and also what they found important to have included in it. These reactions fed into my own art practice and also made the experience more personal, which is significant. In a way, the authority of the artist is invested in the workshop participants, which in turn becomes re-invested in the artist through participant feedback.

Robert Butler: Next to these reactions that you observed, and which feed back into your work, do you also seek to elicit a certain type of response from the public?

Ulrike Hahn: While I have certain pillars that form important values and principles that guide me through my projects, I cannot think of one type of response that I seek to elicit from the public. I can say that for my creative work, such as my abstract art and photography, I highly value that I can pursue open-ended explorations, that there is not necessarily a clear end-goal or solution, that it can be about asking questions or critiquing or challenging something. That is part of the power of the arts, to have that freedom. If authority is defined as the right of certain people to make decisions based on, amongst others, their expertise, I see the artist’s authority as connected to their specific ability to have the freedom to pursue open-ended explorations if the artist so desires. In the research comic project, by some, the comic may be rather seen as accessible communication of the addressed topic, be it the climate crisis or something else. It could perhaps be more clear what type of response is desirable, for example, to inform a certain audience about a concrete research finding, to create some kind of learning. The researcher Julia Bentz (Bentz, 2020), for instance, mentions comics as part of an accessible communication approach (of the topic of climate change). Next to being communicative or a didactic means, I see research comics as having the potential to be more open-ended, process oriented, and transformative. For example, a research comic can be about the researchers’ questions or the research participants’ questions. Or it could include blank spaces, meant to be filled in by the viewer or reader of the comic. This opens up possibilities for comics to move beyond being a ‘communicative tool’ of research. Research comics are not necessarily only intended for the person ultimately engaging with it. They can include sensemaking processes for the creator of the comic. I believe that working on comics, or other art, is not just about creating a finished outcome or achieving a solution, but it is about the process, involving brainstorming, sensemaking, reflection, questioning, collaboration, etc.

Robert Butler: I would like to know who you put in a comic or in your artwork in general. Do you incorporate the researcher or researchers, the student, or maybe a theoretical person? Is it somebody representing a character, a role or an actual person?

Ulrike Hahn: I asked myself this very question, for example for one comic that I made about the findings in other researchers’ studies. Who was going to tell the story in the comic? Who would be talking to the reader of the comic? I used the two researchers and represented them through a fictitious comic character, and I also asked them if they were happy with their portrayal. As two female scientists, it was interesting to showcase their work, because sometimes people automatically assume it is a male academic conducting the research.

Anaïs Augé: Dr Hahn, thank you very much for discussing your work with us on this very relevant theme in multimodality.

Ulrike Hahn: Thank you very much for your questions and for the interesting talk.

Author biographies

Ulrike Hahn holds a PhD degree in the Humanities on climate-related art from Erasmus University Rotterdam and currently works as a freelancer on creative projects, such as research comics, artistic workshops and writing projects.

Anaïs Augé is a FNRS research fellow and Associate Professor at the University of Louvain, Institute of Political Sciences Louvain-Europe and Institute of Language and Communication. Her research focuses on metaphors and argumentation in climate crisis discourse.

Robert Butler is Senior Lecturer at the University of Lorraine, Nancy, France. His research interests include discourse, gesture and cognitive linguistics. Robert Butler is the guest editor of the special issue in which this interview appears.

References

- Balan V., & Dumitrica, D. (2022). Technologies of last resort: the discursive construction of digital activism in Wired and Time magazine, 2010–2021. New Media & Society, Media & Society 26(9): 5466–5485.

- Bentz, J. (2020). Learning about climate change in, with and through art. Climatic Change 162(3): 1595–1612.

- Brand, W. (2019). Visual Doing: Applying Visual Thinking in Your Day-To-Day Business (2nd Printing). Amsterdam: Bis Publishers.

- Brand, W. (2022). Visual Thinking: Empowering People & Organizations through Visual Collaboration (11th Printing). Amsterdam: BIS Publishers.

- Cohn, N. (2021). Who Understands Comics? Questioning the Universality of Visual Language Comprehension. London Bloomsbury Publishing Plc: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Degand, D. (2022). An arts-based inquiry-inspired rubric for assessing college students’ comic essays. Multimodality & Society 2(4): 386–409.

Leave a comment